Moving to a new country, especially one as different and as far away as Japan, always comes with its unique challenges. Never fear – Tokyo Becky is here to help! Here are the Top 10 things that I wish I’d known when moving to Japan, and I hope that these will help you as you settle in to a new place.

1. Bring much more cash than you think you need (also functioning credit cards).

You may be strapped for cash when first moving to Japan but, especially until a few years ago, Japan was a cash-based society, meaning many services and shops did not accept credit cards. Bigger cities are getting better about accepting Visa and Mastercard, but many places in smaller towns still stick to cash only. Big monthly expenses like rent will almost always need to be paid by direct bank transfer or cash in person, so come prepared to spend what may feel like huge amounts of cash at the beginning. It may be up to two months before you receive your first paycheck (especially for English teachers), so bring as much cash as you can.

Japan is also a very safe country and the chances of you being robbed of large amounts of cash that you may be carrying is close to zero….seriously. It may also be useful to alert your credit card companies that you will be living in Japan for the time being, so that your charges will go through. Note: The official customs form for Japan requires you to declare if you are bringing more than 1,000,000 yen being brought into the country (about $9,000).

2. Keep your new Japan Residence Card (Zairyu Card, 在留カード) with you at all times

For those entering Japan on visas that allow them to live and/or work in Japan for more than 90 days, the Japan Residence Card should be issued to you at the airport when you first arrive in Japan once you present your appropriate paperwork. If you happen to fly into an airport that does not have the capability to produce the card for you on-the-spot, the card will be posted to your place of residence after you have registered your place of residence at the office of the city, ward, town or village. This Residence card is like your official ID in Japan and is required by law to be carried with you at all times. Even carrying a passport will not technically suffice if you also have the Residence card. It should be carried and is required for getting a cell phone plan, getting a driver’s license, registering for health insurance or public pension plans, signing up for a gym, etc. It is even required for leaving and entering the country at immigration as a kind of reentry permit on the current visa. In fact, the card, once obtained, also serves as your visa since no official record of your visa is put in your passport. This residence card is your new ID so get used to carrying it around.

3. Unless you are fluent in Japanese, have someone from your company or a trusted fluent Japanese speaker help you set up your bank account in Japan

It’s likely that someone from your company will be required to help you set up your bank form or walk you through the process, but if this is not the case, make sure to bring a trusted Japanese speaker with you. There are several bank account options in Japan, but I recommend setting up a bank account at the Japan Post Office if your company does not already insist on this (the Japan Post Office, while limited in its online banking options is located in every city in Japan, making it very convenient to find your bank everywhere).

Your new company in Japan is going to require you to set up your account with the bank that they already use, but if possible, try to get set up with one of the two largest Japanese banks—Mizuho or SMBC (Sumitomo Mitsui).

In my travels across Japan, I have found them to be the most prevalent. These Japanese banks will have less English assistance but they do offer English as an option on their ATMs in the bank. You may need to bring someone with you when doing something more complicated at the bank office itself. One important tip about setting up an account at a Japanese bank: you will often be required to set up a four digit code secret password for making changes to your account or doing something more complicated than withdrawing money from an ATM. Don’t forget this code. If you sign up for an account using your signature (which I recommend over using a Japanese seal called a hanko, which most Japanese register at the bank using the Chinese characters that make up their name), take a picture of this signature and save it in a safe place. I’ve had friends who could not change their bank accounts years after setting them up because their signatures were not close enough to the original for the bank to approve it!

For those moving to Tokyo, Shinsei Bank has the most English support, but they have a very limited number of physical branches.

http://www.shinseibank.com/english/

4. Find your local ward office and get registered.

In Japan, all cities are separated into separate wards known as “ku.” Some popular wards in Japan are known as Shinjuku-ku, Shibuya-ku, Minato-ku, etc. These “ku” are where your local taxes are handled along with documents required for health insurance, pension systems, trash collection, marriage registry, child services, etc. When first moving to Japan, you have about two weeks to register your new address at the local ward office, so you will definitely get to know this place quickly.

The ward office is also the place that you go to get official documents that include record of payment of local taxes, proof of official residence, information on civic services, parks, local hospitals, etc.

One very beneficial service that the ward office provides are free (or very, very cheap) Japanese lessons to local residents. As an English teacher with student debt, no paycheck for almost two months after arrival, and very little knowledge of Japanese when I first arrived, I found these free language lessons invaluable when I first arrived, not only as a primer for the basics in Japanese, but also as a way to meet people in the community. Lessons are run by volunteers and are often offered between one–three times a week. If you have the time and resources to join a proper Japanese language school, the teachers will likely be of higher quality there, but the ward office lessons are a great place to start.

5. 100 yen ($1) stores are your go-to source for almost everything!

I remember the first Christmas that I was in Japan and was so enamored with the Japanese $1 store (known locally as the 100 yen store) that I bought all of my Christmas gifts there and the shop clerk patiently counted all 85 items aloud. There are several different chains of 100 yen shops (Daiso and Seria are two of the more common—see below) and some carry more merchandise than others, but I mention this to those coming to Japan because this is not the $1 store or discount store that you think of from your own country. The Japanese version of the $1 store has somehow been able to sell things that would sell for 20 times the price in other countries and give it to you for the equivalent of $1. You can find everything from cutting boards and kitchen timers to sleeping masks, travel slippers, and notebooks. Anything that you might need for moving in to your new living space in Japan can be found much cheaper at the 100 yen store. This is perfect for anyone unable to buy a bunch of fancy things when they first arrive in Japan or those who are only coming for one year. It’s not the friendliest to the environment to buy such disposable things, but it’s important to know that this kind of store is available in Japan and is bargain shopping at its finest!

6. Renting an apartment has its own set of rules in Japan. Get familiar with the process.

I’ve now successfully navigated signing contracts with real estate agents for three apartments in Japan, and, let me tell you, doing it yourself is not easy, though there are certain companies that can make it easier. This topic really deserves it own blog post (stay tuned!), but if you are moving to Japan and will not be having an apartment arranged by your company, it might be easiest to initially stay in a guesthouse or AirBnB for one month while first getting settled. If staying in a guesthouse, you will usually have your own bedroom but will share bathroom and kitchen facilities. Every guesthouse has its own rules, but they generally require little money upfront and are friendly to non-Japanese residents (though you will find some that only allow a certain gender, age, or nationality).

The main thing to know about renting your own apartment in Japan is: you will be expected to pay an average of three months rent upfront (and that’s being generous, it can be 4–6 months of rent just to move in) and leases generally last two years but can be broken without penalty. The 4–6 months of rent is usually made up of 1–2 months deposit, 1–2 months of “key money,” a gift that you pay to the landlord for them allowing you to move in. This “key money” is something that you will not be getting back and is a Japanese tradition that is slowly going away, as the variety of housing options has made it easier to avoid this fee. Your real estate agent will also get 1–1.5 months of the price of your new rent for his/her services. Be prepared to pay a lot for moving in!

Many landlords also get very funny about non-Japanese trying to rent from them. I have been shown perfect apartments that no one else was clamoring for, only to be turned down sight unseen because I wasn’t Japanese. This is something that you will need to have your real estate agent screen for at the beginning. Make sure he/she doesn’t show you apartments that you will not even be able to get into in the first place.

Many landlords will also require a “guarantor,” someone that the landlord deems “trustworthy” who can sign a document vouching for you, should you stop paying your rent or suddenly flee the country. This person usually has to be Japanese but can also be the boss at your company. Many companies do act as guarantors for their employees’ apartments but, if you are renting on your own, the company will often make you wait a year before acting as your guarantor. There are now companies that will serve as your guarantor if you want to use an easy, guaranteed option, but this is going to cost another .5–1 months rent for their services.

Finally, monthly utilities for a small apartment will generally cost you around USD 150–200 per month for water, electricity, and gas. Internet and cable will likely run you an extra USD 100 combined.

7. Need some extra money? Teach private lessons in Japan and get paid in cash.

Many English teachers new to Japan take advantage of multiple websites that match freelance teachers with eager students looking to learn a variety of skills for cash in hand (or payment from the third party company, depending on the arrangement). There are a variety of ways to advertise your teaching services, and I’ve seen everything from ads on Craigslist Tokyo to popular free magazines in Japan to word of mouth. Since I arrived in Japan, the typical going rate for private lessons was about JPY 3,000 an hour and could reach up to 10,000 an hour depending on the type of lessons taught, group classes, etc. Some people I know would teach in one of the student’s homes and arrange weekend group classes for 15,000 an hour for the group. Private lesson income can really add up if you set up an effective fee structure and find hard-working, reliable students.

Honestly, most people earning private lesson income accept cash from the students at the end of lesson or upfront for an entire month’s worth of lessons. This is then often not reported on their annual tax returns. Obviously, if you do not report enough Japan-based income on your Japan tax return, Japanese authorities may eventually start getting suspicious, but I will tell you that private lessons are very common in Japan and many people make considerable extra income each month through this system. Most lessons are taught in local cafes, parks, or public spaces. This may be a great way to make extra money when you first arrive if you’re low on cash. Here are a few websites to get you started:

http://www.121sensei.com/index.php

8. Meeting new people is not as hard as you think.

I was lucky when I first came to Japan because I worked for a huge English teaching company in Tokyo with many new employees from around the world arriving each week. From day one, I was in company housing with fellow employees and was able to make friends right away. For many others arriving to work for Japanese corporations, it is not so easy. Japan can be an isolating place if you don’t speak the language and can’t read the information around you.

Thankfully, we are in the internet age and many people have come before you, so you have a variety of options for how to meet people. One of my favorites is www.meetup.com, originally from New York City but now a worldwide tool to help you meet like-minded people with similar interests. Meetup.com has groups based all over Japan and new groups are being formed daily. I met some of my closest friends in Tokyo through meetup.com.

Another place to meet someone is at your local ward office at free language lesson classes (see #4). The Japanese teachers there are all volunteers and the students are in the same boat as you trying to figure out life in Japan, so you may find yourself getting invited to a local Japanese home or meeting a new neighbor living in the same ward. One bonus to meeting people here is that they are guaranteed to live close by since they are going to the same ward office for language lessons.

I’ve also met a number of people by just attending classes for something that I was interested in. For example, I wanted to try Japanese calligraphy, found a class online in Tokyo, attended the lesson, and met two new friends there. It’s really just that simple!

Many people new to Japan also find a neighborhood bar that becomes their “local” place to relax after a long day of work or have a simple drink with other bar regulars. I’ve lived in a number of different neighborhoods and every time that I’ve found my new “local” place, the Japanese regulars there opened up to me on the first, if not the second visit. Best friends can be made at the “local.” Find your favorite local bar and you could make friends for life.

9. Run, don’t walk, to get your commuter pass.

This one can be tricky for those who must work at a number of different places throughout the week (common for teachers in big cities in Japan), but if you are commuting daily from your home to the same location, it is a very wise financial decision to buy a monthly train commuter pass. By law in Japan, employers are required to reimburse employees for the cost of a monthly commuter pass. However, I’ve met some employees who only use their Pasmo train cards and just continue to top up the balance on their cards with cash, essentially paying cash for their monthly commute and being reimbursed a portion of it by their employers at the end of the month.

DO NOT DO THIS! BUY THE COMMUTER CARD—because every train station in between your home station and the final train destination is free to visit during the month of coverage. This can really pay off if your commute includes a train line that has several popular destinations on it. For example, my train pass includes stops near Yoyogi Park, Omotesando (a trendy shopping area), and the Imperial Palace. If I want to visit these places on days when I’m not working, I can get to all of them for no extra charge for the entire month. Considering that a base one-way ticket costs $1.50 on the Tokyo metro, this can really add up.

Commuter passes can be purchased from certain ticket machines at the train station. The minimum period that can be purchased is one month. Three-month and six-month options are also available for slightly discounted prices. You can also have your name, phone number, age, home train station and final destination printed on the front of the card. This way, if you lose the card, you may be contacted if someone finds it and turns it in. The commuter passes are also partially refundable if you lose your card and report the loss at the train station.

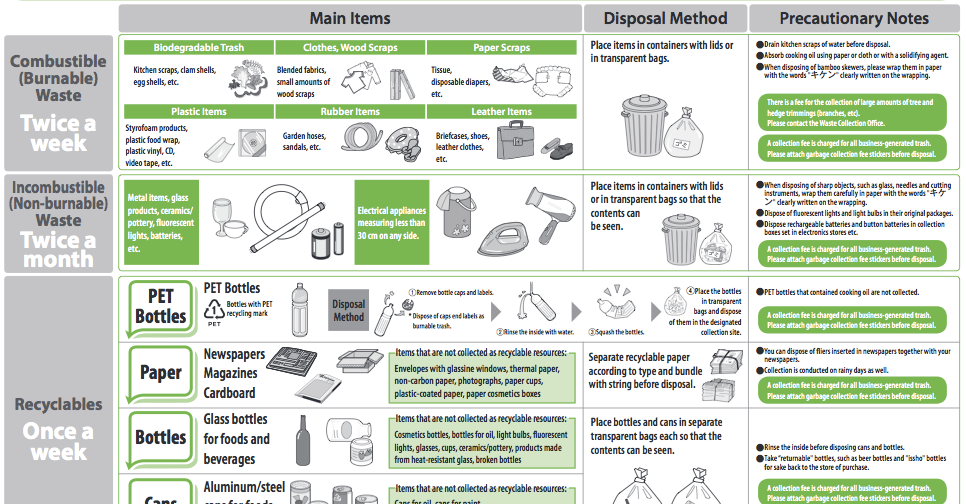

10. Throwing away your trash is a science. Learn your district’s rules at the ward office.

When I lived in the suburban U.S., throwing away trash was easy…too easy when I think about. In fact, we had a huge landfill that had long been known as a local “mountain” of trash a fifteen-minute drive away. We threw everything out together on the same curb once a week, and had a small red box for recycling on that same day. None of the recycling had to be sorted. Looking back, I don’t know how the trash ever got sorted once they picked it up.

In Japan, a much more densely populated nation, especially in big cities, the onus is much more on the individual to carefully sort their own trash and know the rules for when to dump it. Let me give you an example based on my own neighborhood:

Mondays and Thursdays: regular trash pick-up (paper and plastic can, happily, be put in the same trash bag, but the trash should be of a “combustible” nature and should not include cardboard)

Wednesdays: Pick-up for cardboard, glass bottles and cans (should be sorted separately in the bins provided)

Saturdays: (1st and 3rd Sundays)–PET bottle (or plastic bottle) pick-up

(2nd and 4th Saturdays)–bulky, unburnable trash that is generally not bigger than a trash bag itself. If it is electronic in nature or includes batteries, it cannot be thrown out on this day.

Any big items that need to be thrown away must be arranged with the local ward office. You must call a number, arrange a time for pick-up, buy a certain amount of stickers from the convenience store that will cover the cost of pick-up based on the weight and height that you give to the ward office representative, and set out the item on the street shortly before the pick-up time.

This is complicated, right? In some neighborhoods, it’s even more complicated because paper and plastic of a certain type must be separated further. Oh yeah, and your cardboard? It better be broken down and tied together with string so it’s easy to throw away with the tape removed and thrown away into the main trash. People who don’t follow the trash rules have been known to have their trash returned to them in front of their apartment doors by nosy neighbors.

The ward office and/or your real estate agent will teach you the trash collection system and you should learn it quickly for best results. I put a cheat sheet on my refrigerator for the first couple of months.

In case of emergency:

Last but not least, if you have emergency or fire, call 119 for the ambulance.

To talk to the police, call 110.

umm I for one loved this…I am still considerably too young to move to Japan on my own, but I found this very helpful for what I hope is going to be my future…thank you very much 🙂