This is not the first time that I’ve written about Shimokitazwa, Tokyo’s coolest neighborhood, but it’s the first time I’ve shared my personal stories with you in my blog. As I shared in my first post about Shimokitazawa, I had the good fortune to first set foot in what I still believe is Tokyo’s coolest neighborhood all the way back in 2004. I had never heard of Shimokitazawa when I was first assigned to work in an English school there called Nova. Three days after arriving in Japan for the first time, I paid my first visit to the neighborhood that would literally change my life.

Shimokitazawa: The Backstory

Shimokitazawa in 2004 was a hive of energy, a mishmash of streets, smells, and smiles. At the time, the neighborhood still had its old train station, which would spit you out right at street level in a square full of street performers, college kids smoking cigarettes on benches, and musicians with guitars strapped to their backs. It was a place where anything and everything felt like it could happen if you turned the right corner.

Within my first week of working in Shimokitazawa, after meeting a rag tag international band of enthusiastic teachers in their early 20s including my boss, Ben, who couldn’t have been more than 25 and already smoked out the window of our teacher’s break room with the fervor of an overworked Japanese salaryman in their 40s, I was hooked on the neighborhood.

Ben S. (not Ben M., my aforementioned boss) took me on my first true tour of the neighborhood. He may have won the prize for quirkiest teacher in our school. Not only did he always wear a black trench coat to school but he also carried a large matching duffel bag stuffed to the brim with plastic bottles full of water. “It’s my free workout every day,” he said. “Try to lift this” pointing to the bag on the break room floor to which I would groan even attempting it. “How many bottles do you have in here, Ben?” “At least 25 last time I checked.” I had no idea how Ben S. carried his duffel bag on the one-hour commute to Shimokitazawa every day, but his muscles were quite hard when he asked me to touch them.

Luckily, Ben S. and I had a break at the same time on my first day, and he offered to take me around the neighborhood for lunch. That first day, I had absolutely no idea where we were going. We must have made at least six turns through the neighborhood looking at stores that Ben pointed out on our way to the place he wanted to patronize. One moment we were standing in front of a shop selling the most “kawaii” socks and the next we were deep in the belly of the department store straight out of the 1970s lost in the ever twisting aisles of a Japanese bookstore/record shop hybrid called Village Vanguard, which you can still visit today. Ben S. eventually took me to a place called “Mois” in a 60-year-old house filled with old furniture that served Japanese soul food. “Tomorrow, I can take you to Masako, a jazz cafe around the corner that’s been open since the 1950s,” Ben said. “Definitely one of my favorite places.”

Moving to Shimokitazawa: Tokyo’s Coolest Neighborhood

I ended up spending only six months working in Shimokitazawa before taking on an assistant trainer position at a bigger English school farther out in the suburbs. I didn’t have much of a choice as my school was small and once you were trained, there was an imperative to send you to more challenging locations. I cried on my last day, as I already felt that Shimokitazawa was my favorite place. If I couldn’t work there anymore, I vowed to return and live there instead, even if it meant having a long commute.

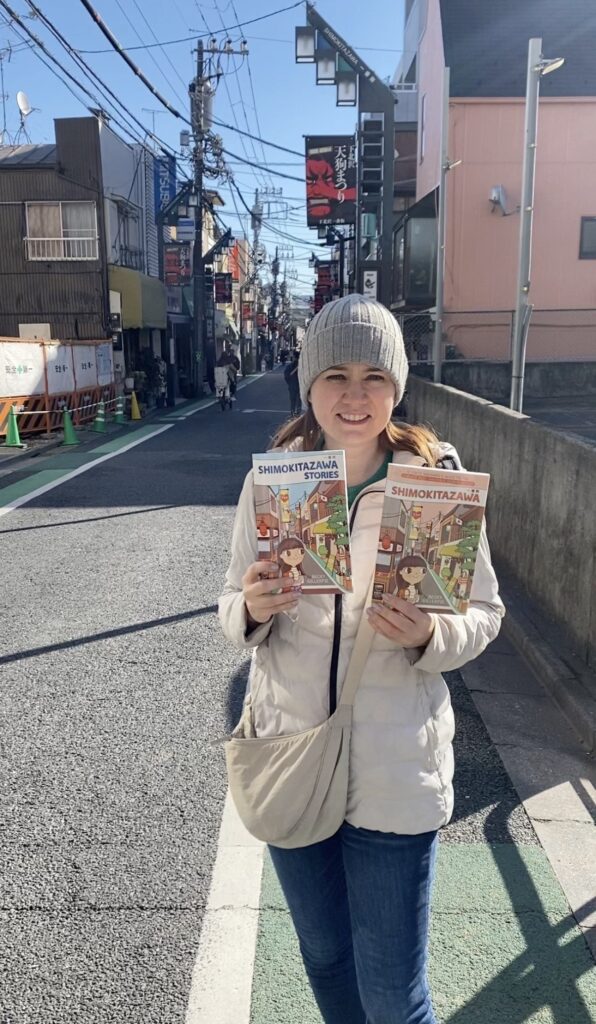

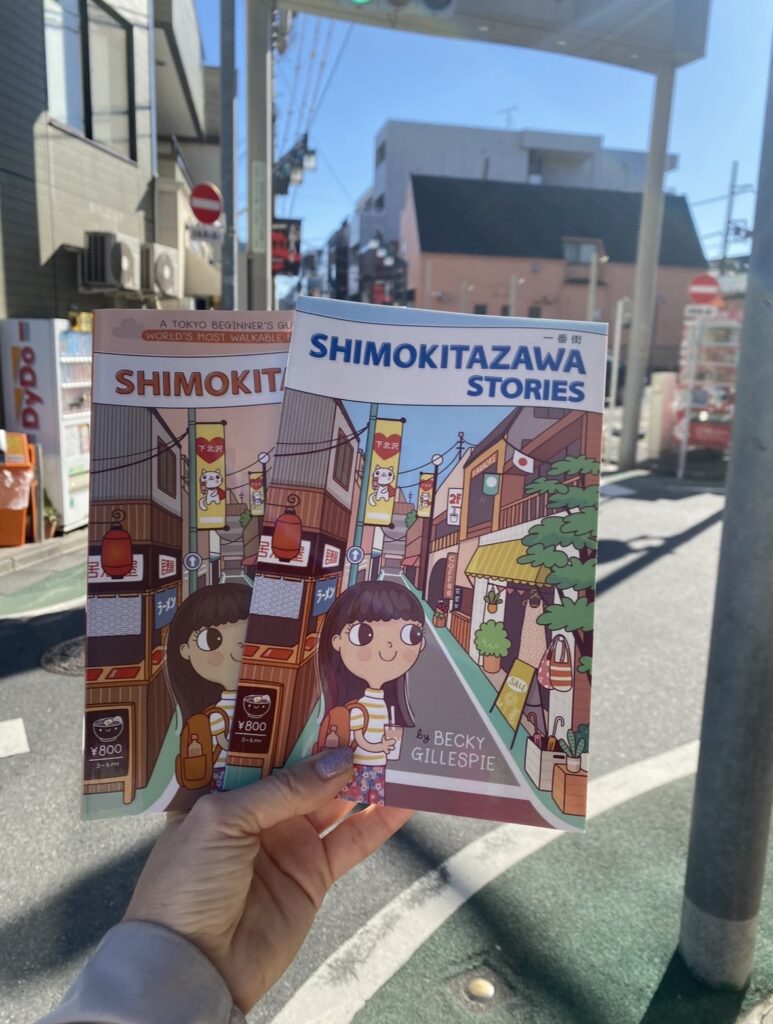

I would get my wish four years later when I got a job with a big accounting firm in the center of the city. No longer a teacher, I felt that I finally had the money to afford to live in Tokyo’s coolest neighborhood. I would end up living in Shimokitazawa for nine years, in two different apartments and one guesthouse. By the end of my time there, I decided to write a guidebook to the neighborhood, which I ended up publishing in 2020. The final title was “Shimokitazawa: A Tokyo Beginner’s Guide to the World’s Most Walkable Neighborhood,” and you can still buy it here. This book includes both the guidebook and short stories.

After the first version of my book was released, a few readers asked me to write some stories about my time in Shimokitazawa rather than just include cafés or the best places to buy vintage clothing or records (two other things that Shimokitazawa is famous for). So, I got back to work and reflected over my nine years in the neighborhood. Eventually, I finished seven stories and published them separately in a book I called “Shimokitazawa Stories.“

As the final part of my post here today, I’d like to include one of the stories for you, and I’d love to hear what you think. To me, Shimokitazawa is a place full of magical possibilities. I hope that reading this story inspires you to visit and find your own magic. You can use my guidebook to help or discover your own Shimokitazawa power spots. Things are always changing in Tokyo’s coolest neighborhood, so you never know what you are going to find!

Shimokitazawa Story – “Your Drug Is a Heartbreaker”

Late one night on a walk back to my apartment place on the road to Sangenjaya, I stopped by my favorite takoyaki place, the one with the window, shutters often open, looking onto the road beckoning customers to stop and chat for a spell. I had loved this takoyaki place for a while, stopping by several times in the past to enjoy the chewy

bit of the tentacle underneath the fried dough and brown sauce.

Bando, the proprietor, was the kind of warm and friendly worker who personifies the Shimokitazawa spirit and had the air of someone who had never let office life steal his joy and drain his personality of its radiance. I decided to stop in for a few bites of deliciousness in an attempt to punctuate my day with something other than the endless hours at the office and my bed.

When I arrived, I noticed that Bando wasn’t at his usual place at the window. Instead, he was inside behind the 5-chair bar that extended across the small interior with only two tiny free-standing tables. Bando greeted me with his usual beaming smile and gestured towards a man with what looked like an instrument strapped to his back, chatting in a low but animated voice to the bartender.

“Hi. I’m Morita. Where are you from?”

I smiled, acknowledging the nearly universal question that Japanese people like to start with when addressing someone who clearly did not look Japanese.

“I’m Becky and I’m from the USA.”

“Nani-shu desu-ka? What state are you from?”

“Ohio”

“Ahhh Ohio. Ohayo gozaimasu. Good morning!”

I smiled again, always finding the linguistic pun that links my first and second home charming, remembering the first time my grandfather, a Korean War veteran, had told me of the Ohio/ohayo joke the age of six, as he sat on a deck chair on his back patio.

Before could say anything further, Moria turmed back to Bando.

“Play some Weezer. She is American. We need some American music.” Bando laughed and suddenly the strains of “Say It Ain’t So” came on and I grinned even wider because it was one of only two Weezer songs I actually knew.

Suddenly, the bar had turned into karaoke session, as Morita and I sang “My love is a life taker” in almost perfect unison, continuing together for the rest of the song. By the end of our impromptu performance, the drab hours spent in my office had melted away and I was in a California band, singing backup for Morita.

“I have four children,” he said randomly at the end of the song.

An oddity for Japan these days, I thought.

“I am a musician,” slapping his heart as if to keep it beating.

“And she…” he said, suddenly acknowledging the only other custome in the bar. “She is a drummer. Her name is Yamamoto.” A polite, middle-aged woman in what appeared to be her early 20s grinned and shouted,”Ohayo!“

Was she talking about my state again?

“Konbanwa!”

After bidding her good evening, I found myself thrust into a mainly Japanese conversation, all of us several beers in.

“T’m Yamamoto. Yoroshiku onegaishimasu, nice to meet you.”

She punctuated the last sentence with a cute little bow.

“Drummer desu.”

I asked if they ever played together.

“Un. Tokidoki. Yeah, sometimes. At Never Never Land (another bar in Shimokitazawa)

“Watashi mo OL desu.”

“O…L?” I said, completely at a loss for what she might be saying.

“Oh-eru… you work in the oil industry?!”

“Un“

I was shocked. How was this woman in her 20s not only able to get a job in the male-dominated world of the oil industry but also be a drummer in a Shimokitazawa band? She was the first woman i dever met who worked in the oil industry. Or so I thought.

It was only later when I checked with a friend that I discovered that OL meant “office lady”, a common term in Japan for women who worked in a general position in an office, as it was not customary to

describe your role in detail. OL usually covered it all.

But on that night, in my mind, Yamamoto was a high-powered oil industry executive who arranged barrel delivery by day and drummed by night on the Shimokita stage.

Just as the last refrain of “Buddy Holly” faded away, Morita came back from a singing reverie, looked deep into my eyes (a surprise, as many people in Japan tend to avoid eye contact to maintain their own space and privacy.

“Becky from Ohio. Becky from Ohio. I know you. And I am going to play a song for you. Now, I will play and you will sing the words.

I know you know this song already and you don’t need the words. You sing and I play, ok?

Fully in Morita’s trance, I nodded as he pulled his guitar out and started to tune the strings. Transfixed, I watched his fingers move up and down the black guitar, wondering what he would play that a girl from Ohio would surely know. Suddenly, his hands slowed, and he started playing a refrain. As he repeated it, I audibly gasped and the biggest smile of my life took over my face. I knew the song Morita was playing; in fact, it was one of the few songs that I had ever taught myself to play. He repeated the refrain for the second time and I joined in without needing to look up the lyrics, without question.

It was as if he had peered into my soul and saw the words deep inside.

Not only was it a song I knew by heart, but a melody from my favorite film trilogy of all time, a song I had practiced over and over but never in the presence of someone who actually understood its context. In “Before Sunrise,” the second film of Richard Linklater’s Before Trilogy Julie Delpy sings a song called “A Waltz for a Night” for her lover Jesse, right before he leaves for the airport, possibly to never see her again. (I won’t give away any more, as seeing these films is one of the greatest cinematic gifts you can give yourself.)

Who was this guy, in this bar, who didn’t speak a word of English, who appreciated a cinematic masterpiece to the point where he also learned the intro, the verses, the bridge, and the refrain? I knew for a fact that this song was not available at any of the karaoke bars in Japan, because I always hoped it would appear as I scoured the pages.

Perhaps he had been like me: so equally transfixed and charmed by the moment that Julie Delpy picked up the guitar that I felt compelled to learn it.

I finished singing and Morita smiled. Yamamoto and Bando clapped.

The only sound to be heard was the sizzle of takoyaki balls in the background, as Morita and I held each other’s gaze.

“I know you,” Morita said, again looking deep into my eyes.

A thousand thoughts rushed through my head, but astonishment won out. Never had I encountered such a moment of pure coincidence, kismet pulling Morita towards the same takoyaki place that we probably loved for the same reasons—the homey feeling Bando created in this tiny hole-in-the-wall, full of music and love for the moments customers could spend together.

Morita gently put his guitar back into its case and swung it back onto his shoulders. He tapped the table with his right palm looking at Bando, me, Yamamoto. “I have to go.”

I followed him out, the streets of Shimokita empty and the warm night taking us into its embrace. Suddenly, Morita turned around and waved his arms in the air, pointing at the large devilish-looking dragon surrounded by a blaze of red, yellow, and orange flames, fanning itself above the entrance of the bar. I had always admired this mythological creature. “I drew that,” he said, and my jaw dropped for the second time in the evening, the encounter growing even wilder.

“My name is Morita. If you ever need me, just call my name.”

“I will” I replied, looking into his eyes one last time, taking in his entire presence—the guitar, black leather, biker glasses, the connection. Then, he turned and disappeared down a side street.

I never saw him again. I didn’t need to.

0 Comments